Solutions détaillées de neuf exercices sur les coefficients binomiaux (fiche 02)

Cliquer ici pour accéder aux énoncés

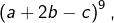

Dans l’expression développée de  les termes en

les termes en  s’obtiennent en sélectionnant

s’obtiennent en sélectionnant  dans 4 parenthèses, ce qui peut se faire de

dans 4 parenthèses, ce qui peut se faire de  façons et, pour chaque tel choix, en sélectionnant

façons et, pour chaque tel choix, en sélectionnant  dans 3 parenthèses parmi les 5 restantes, ce qui peut se faire de

dans 3 parenthèses parmi les 5 restantes, ce qui peut se faire de  façons (il reste ensuite 2 parenthèses où l’on doit fatalement sélectionner

façons (il reste ensuite 2 parenthèses où l’on doit fatalement sélectionner

Le coefficient de  dans le développement de

dans le développement de  est donc :

est donc :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\binom{9}{4}\binom{5}{3}2^{3}\left(-1\right)^{2}=\frac{9\times8\times7\times6}{4\times3\times2}\:\frac{5\times4}{2}\:8=\boxed{10080}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ef6484db9b9cb99680e4f4b366f4b7f9_l3.png)

Pour tout entier  la formule de Pascal donne :

la formule de Pascal donne :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\binom{2n}{n}=\binom{2n-1}{n-1}+\binom{2n-1}{n}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d2d1fce2765acc436cc815dcb178cb0d_l3.png)

Mais d’après la formule de symétrie :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\binom{2n-1}{n-1}=\binom{2n-1}{\left(2n-1\right)-\left(n-1\right)}=\binom{2n-1}{n}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-553d4d45cf550818860fa9624b3a472c_l3.png)

et donc :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\binom{2n}{n}=2\thinspace\binom{2n-1}{n}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-053d34521d723e4380fb3517287c9c07_l3.png)

ce qui prouve la parité de

Noter que pour

cet entier est impair (il vaut 1).

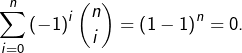

On sait que :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\binom{n}{k}=\frac{n\left(n-1\right)\cdots\left(n-k+1\right)}{k!}=\prod_{j=0}^{k-1}\frac{n-j}{k-j}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7a92a5b79776b98cca7cc401fddb0ea0_l3.png)

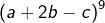

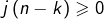

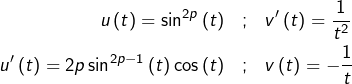

Si l’on prouve que, pour tout

:

( )

) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{n-j}{k-j}\geqslant\frac{n}{k}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-bbdc02c7849c20773b31200b26b9807b_l3.png)

il en résultera que :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\boxed{\binom{n}{k}\geqslant\left(\frac{n}{k}\right)^{k}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ac6c291b5cecdb4e0e2b9e80f066d770_l3.png)

Or l’inégalité

équivaut à :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\left(n-j\right)k\geqslant n\left(k-j\right)\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-681fa9016d8620d535896e76a4070061_l3.png)

donc aussi à

, qui est évidemment vraie.

Soient  des entiers tels que

des entiers tels que  D’après la formule de Pascal :

D’après la formule de Pascal :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}\sum_{i=0}^{k}\left(-1\right)^{i}\binom{n}{i} & = & 1+\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(-1\right)^{i}\left[\binom{n-1}{i}+\binom{n-1}{i-1}\right]\\& = & 1+\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left[\left(-1\right)^{i}\binom{n-1}{i}-\left(-1\right)^{i}\binom{n-1}{i-1}\right]\end{eqnarray*}](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5f7e4182a498d051b226dadee74727d8_l3.png)

On a fait apparaître une sommation télescopique. Au final :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sum_{i=0}^{k}\left(-1\right)^{i}\binom{n}{i}=\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{n-1}{k}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9c4871dfa610f721d8724d5cfc0e0e54_l3.png)

Notons  cette somme. On peut la séparer en deux :

cette somme. On peut la séparer en deux :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[S_{p}=\sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}+\sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k-1}\binom{2p}{k-1}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b8b7e996a0b5c17e5af8af3ae27d648f_l3.png)

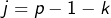

puis effectuer, dans la dernière somme, le changement d’indice

On obtient :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[S_{p}=\sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}+\sum_{j=p+1}^{2p}\left(-1\right)^{2p-j}\binom{2p}{2p-j}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f352ad279ce84cb559d39d30ef57cbca_l3.png)

et donc, par symétrie des coefficients binomiaux :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[S_{p}=\sum_{k=1}^{2p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}=-1+\left(1-1\right)^{2p}=-1\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-113ee995601c6986c0c98b4f83c68e97_l3.png)

Remarque

On peut aussi exploiter le résultat de l’exercice précédent :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}S_{p} & = & \sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\left[\binom{2p}{k}-\binom{2p}{k-1}\right]\\& = & \sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}+\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}\\& = & -1+\sum_{k=0}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}+\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}\end{eqnarray*}](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c3d97c48e8eeba6c319691a9a2af419e_l3.png)

d’où la conclusion, puisque les deux dernières sommes valent 0 (d’après l’exercice n° 4).

Si l’on connaît la formule de Stirling :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[n!\sim\left(\frac{n}{e}\right)^{n}\sqrt{2\pi n}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9ba8dcc6f5250b8f4e09320a96ea0100_l3.png)

on voit aussitôt que :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\binom{2n}{n}=\frac{\left(2n\right)!}{\left(n!\right)^{2}}\sim\frac{\left(\frac{2n}{e}\right)^{2n}\sqrt{4\pi n}}{\left(\left(\frac{n}{e}\right)^{n}\sqrt{2\pi n}\right)^{2}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-41bb2b9701d6796aae2b75300a15e716_l3.png)

c’est-à-dire :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\boxed{\binom{2n}{n}\sim\frac{4^{n}}{\sqrt{\pi n}}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-4dfecdc81992e0281d84fd5b83a78abf_l3.png)

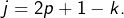

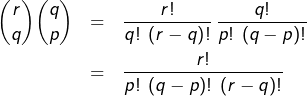

Commençons par une preuve algébrique (calculatoire … donc pas passionnante). D’une part :

et d’autre part :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}\binom{r}{p}\binom{r-p}{q-p}&=&\frac{r!}{p!\:\left(r-p\right)!}\thinspace\frac{\left(r-p\right)!}{\left(q-p\right)!\:\left[\left(r-p\right)-\left(q-p\right)\right]!}\\&=&\frac{r!}{p!\:\left(q-p\right)!\:\left(r-q\right)!}\end{eqnarray*}](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-79c91b5bdf44ecb78fd3a576eb1210db_l3.png)

de sorte que :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\boxed{\binom{r}{q}\binom{q}{p}=\binom{r}{p}\binom{r-p}{q-p}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-de82362c3bb392d99e0c0a85911f8210_l3.png)

Passons à une preuve

combinatoire. Etant donné un ensemble

de cardinal

calculons le nombre

de couples

de parties de

tels que :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\text{card}\left(F\right)=q,\quad\text{card}\left(G\right)=p\quad\text{et}\quad G\subset F\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-cfb82b4295aac7aae769596ad33dc811_l3.png)

Une première méthode consiste à choisir d’abord

, ce qui peut se faire de

façons. Pour chaque tel choix, il existe

façons de choisir

Ainsi :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[N=\binom{r}{q}\binom{q}{p}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-263ef55cacf3143bc402521c6eaeab5e_l3.png)

Seconde méthode : on choisit d’abord

ce qui peut se faire de

façons. Pour chaque tel choix, il existe

façons de choisir

(en effet, vu qu’on a déjà choisi

éléments, il faut « entourer »

en sélectionnant

éléments parmi les

qui restent). Ainsi :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[N=\binom{r}{p}\binom{r-p}{q-p}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-df8a058299a25cf9835d737e36f7e9ad_l3.png)

et l’on retrouve bien la formule encadrée.

Remarque

Pour  et toujours

et toujours  , cette formule devient :

, cette formule devient :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[q\binom{r}{q}=r\binom{r-1}{q-1}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f42d9c85d233b942f210ca3751b1a2fe_l3.png)

On reconnaît la fameuse « formule du pion » (voir la section 7 de

cet article)

Calculons, pour tout entier  :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[J_{p}=\int_{0}^{+\infty}\dfrac{\sin^{2p}\left(t\right)}{t^{2}}\thinspace dt\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-3e9dc285a593b94ce5a0f4656efa5b29_l3.png)

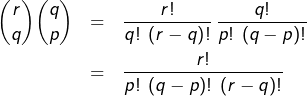

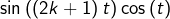

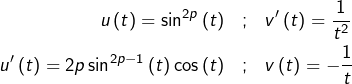

Si l’on intègre par parties en posant :

il vient :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[J_{p}=2p\int_{0}^{+\infty}\dfrac{\sin^{2p-1}\left(t\right)\cos\left(t\right)}{t}\thinspace dt\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e49b7f52bfd531787e62f12f936be474_l3.png)

La

formule de linéarisation :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sin^{2p-1}\left(x\right)=\frac{1}{4^{p-1}}\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p-1}{p-1-k}\sin\left(\left(2k+1\right)x\right)\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d1d5b311f6d5442ebd81129beda4862d_l3.png)

donne alors :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[J_{p}=\dfrac{2p}{4^{p-1}}\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p-1}{p-1-k}\int_{0}^{+\infty}\dfrac{\sin\left(\left(2k+1\right)t\right)\cos\left(t\right)}{t}\thinspace dt\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b062ca0a969baaace35d3a7b1a4c7581_l3.png)

c’est-à-dire, après transformation du produit

en somme :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[J_{p}=\dfrac{p}{4^{p-1}}\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p-1}{p-1-k}\int_{0}^{+\infty}\dfrac{\sin\left(\left(2k+2\right)t\right)+\sin\left(2kt\right)}{t}\thinspace dt\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-2aa12621cbb5b03683282eb84f874135_l3.png)

Or on sait (intégrale de Dirichlet) que :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\int_{0}^{+\infty}\dfrac{\sin\left(t\right)}{t}\thinspace dt=\dfrac{\pi}{2}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-1451b846132166990d1f57cb04fd9216_l3.png)

et donc, pour tout

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\int_{0}^{+\infty}\dfrac{\sin\left(\left(2k+2\right)t\right)+\sin\left(2kt\right)}{t}\thinspace dt=\left\{ \begin{array}{cc}\pi & \text{si }k\geqslant1\\\\\dfrac{\pi}{2} & \text{si }k=0\end{array}\right.\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-a54857a639c8484a3f8adfec6dc30c44_l3.png)

Par conséquent :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[J_{p}=\dfrac{p\pi}{2^{2p-1}}\left[\binom{2p-1}{p-1}+2\sum_{k=1}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p-1}{p-1-k}\right]\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-6435cf83df1bfa4e8ad6e5e2090e24b0_l3.png)

Dans cette dernière somme, on peut poser

et utiliser le résultat de l’exercice n° 4 :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}J_{p} & = & \dfrac{p\pi}{2^{2p-1}}\left[\binom{2p-1}{p-1}+2\left(-1\right)^{p-1}\sum_{j=0}^{p-2}\left(-1\right)^{j}\binom{2p-1}{j}\right]\\& = & \dfrac{p\pi}{2^{2p-1}}\left[\binom{2p-1}{p-1}-2\binom{2p-2}{p-2}\right]\end{eqnarray*}](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8af88aff72de817b0c4e4a88e9dfc0c5_l3.png)

En définitive :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\boxed{J_{p}=\dfrac{\pi}{2^{2p-1}}\binom{2p-2}{p-1}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-898d88aa005ac29157850616e39dfc20_l3.png)

- L’application qui, à une chaine

associe la permutation

associe la permutation  définie par

définie par ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\forall i\in\left\llbracket 1,n\right\rrbracket ,\thinspace\left\{ \sigma\left(i\right)\right\} =C_{i}-C_{i-1}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-61439e3cbb16bcb344f1ba1da2259123_l3.png)

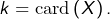

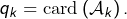

est une bijection. Il existe donc  chaînes. Soit maintenant

chaînes. Soit maintenant  une partie de

une partie de  Notons

Notons  Dire que

Dire que  fait partie d’une chaîne

fait partie d’une chaîne  signifie que

signifie que  Il existe

Il existe  façons de contruire la sous-chaîne

façons de contruire la sous-chaîne  puis, pour chaque tel choix,

puis, pour chaque tel choix,  façons de prolonger celle-ci en une chaîne. Au total, le nombre de chaînes « passant par

façons de prolonger celle-ci en une chaîne. Au total, le nombre de chaînes « passant par  » est

» est

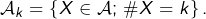

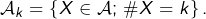

- Pour tout

l’ensemble des parties de

l’ensemble des parties de  qui sont de cardinal

qui sont de cardinal  est une antichaîne, de cardinal

est une antichaîne, de cardinal  En particulier pour

En particulier pour

- Une majoration :

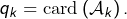

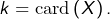

- Pour tout

notons

notons  Par définition :

Par définition :  Comme

Comme  on voit en passant aux cardinaux que :

on voit en passant aux cardinaux que : ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[{\displaystyle \sum_{k=0}^{n}q_{k}}=r\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-56fcf77a20ccb3def346b270077fdb49_l3.png)

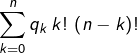

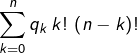

Pour chaque  et pour chaque élément

et pour chaque élément  on considère les

on considère les  chaînes qui passent par

chaînes qui passent par  Ceci représente un total de

Ceci représente un total de  chaînes, car une même chaîne ne peut pas passer par deux éléments distincts de

chaînes, car une même chaîne ne peut pas passer par deux éléments distincts de  (sans quoi il existerait une relation d’inclusion entre ces deux éléments de

(sans quoi il existerait une relation d’inclusion entre ces deux éléments de  ce qui est absurde). Ce total étant majoré par le nombre chaînes, il vient :

ce qui est absurde). Ce total étant majoré par le nombre chaînes, il vient : ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}q_{k}\thinspace k!\thinspace\left(n-k\right)!\leqslant n!\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-39e5a0ee4ae8bd34082c4c24db8a217b_l3.png)

- L’inégalité précédente peut s’écrire :

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}\frac{q_{k}}{\binom{n}{k}}\leqslant1\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-4953a1f645e9c49eb1e884b163e2bb2a_l3.png)

Or, on sait que : ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\forall k\in\left\llbracket 0,n\right\rrbracket ,\thinspace\binom{n}{k}\leqslant\binom{n}{\left\lfloor \frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor }\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e4611ed39ae8e90c2d8933c3ca628d61_l3.png)

Il s’ensuit que : ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}q_{k}\leqslant\binom{n}{\left\lfloor \frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor }\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-2a9435892a79bdf8e22054a7df7e16ee_l3.png)

c’est-à-dire (cf. 3°-A) : ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[r\leqslant\binom{n}{\left\lfloor \frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor }\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-63e723f2631b0709e1403c97bd01e488_l3.png)

Compte tenu du 2°, on conclut que le cardinal maximal d’une antichaîne est

Si un point n’est pas clair ou vous paraît insuffisamment détaillé, n’hésitez pas à poster un commentaire ou à me joindre via le formulaire de contact.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\binom{n}{k}=\frac{n\left(n-1\right)\cdots\left(n-k+1\right)}{k!}=\prod_{j=0}^{k-1}\frac{n-j}{k-j}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7a92a5b79776b98cca7cc401fddb0ea0_l3.png)

![]() )

) ![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\boxed{\binom{n}{k}\geqslant\left(\frac{n}{k}\right)^{k}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ac6c291b5cecdb4e0e2b9e80f066d770_l3.png)

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}\sum_{i=0}^{k}\left(-1\right)^{i}\binom{n}{i} & = & 1+\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(-1\right)^{i}\left[\binom{n-1}{i}+\binom{n-1}{i-1}\right]\\& = & 1+\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left[\left(-1\right)^{i}\binom{n-1}{i}-\left(-1\right)^{i}\binom{n-1}{i-1}\right]\end{eqnarray*}](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5f7e4182a498d051b226dadee74727d8_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sum_{i=0}^{k}\left(-1\right)^{i}\binom{n}{i}=\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{n-1}{k}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9c4871dfa610f721d8724d5cfc0e0e54_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[S_{p}=\sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}+\sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k-1}\binom{2p}{k-1}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b8b7e996a0b5c17e5af8af3ae27d648f_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[S_{p}=\sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}+\sum_{j=p+1}^{2p}\left(-1\right)^{2p-j}\binom{2p}{2p-j}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f352ad279ce84cb559d39d30ef57cbca_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[S_{p}=\sum_{k=1}^{2p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}=-1+\left(1-1\right)^{2p}=-1\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-113ee995601c6986c0c98b4f83c68e97_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}S_{p} & = & \sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\left[\binom{2p}{k}-\binom{2p}{k-1}\right]\\& = & \sum_{k=1}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}+\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}\\& = & -1+\sum_{k=0}^{p}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}+\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p}{k}\end{eqnarray*}](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c3d97c48e8eeba6c319691a9a2af419e_l3.png)

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\binom{2n}{n}=\frac{\left(2n\right)!}{\left(n!\right)^{2}}\sim\frac{\left(\frac{2n}{e}\right)^{2n}\sqrt{4\pi n}}{\left(\left(\frac{n}{e}\right)^{n}\sqrt{2\pi n}\right)^{2}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-41bb2b9701d6796aae2b75300a15e716_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\boxed{\binom{2n}{n}\sim\frac{4^{n}}{\sqrt{\pi n}}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-4dfecdc81992e0281d84fd5b83a78abf_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}\binom{r}{p}\binom{r-p}{q-p}&=&\frac{r!}{p!\:\left(r-p\right)!}\thinspace\frac{\left(r-p\right)!}{\left(q-p\right)!\:\left[\left(r-p\right)-\left(q-p\right)\right]!}\\&=&\frac{r!}{p!\:\left(q-p\right)!\:\left(r-q\right)!}\end{eqnarray*}](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-79c91b5bdf44ecb78fd3a576eb1210db_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\boxed{\binom{r}{q}\binom{q}{p}=\binom{r}{p}\binom{r-p}{q-p}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-de82362c3bb392d99e0c0a85911f8210_l3.png)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sin^{2p-1}\left(x\right)=\frac{1}{4^{p-1}}\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p-1}{p-1-k}\sin\left(\left(2k+1\right)x\right)\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d1d5b311f6d5442ebd81129beda4862d_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[J_{p}=\dfrac{2p}{4^{p-1}}\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p-1}{p-1-k}\int_{0}^{+\infty}\dfrac{\sin\left(\left(2k+1\right)t\right)\cos\left(t\right)}{t}\thinspace dt\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b062ca0a969baaace35d3a7b1a4c7581_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[J_{p}=\dfrac{p}{4^{p-1}}\sum_{k=0}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p-1}{p-1-k}\int_{0}^{+\infty}\dfrac{\sin\left(\left(2k+2\right)t\right)+\sin\left(2kt\right)}{t}\thinspace dt\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-2aa12621cbb5b03683282eb84f874135_l3.png)

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\int_{0}^{+\infty}\dfrac{\sin\left(\left(2k+2\right)t\right)+\sin\left(2kt\right)}{t}\thinspace dt=\left\{ \begin{array}{cc}\pi & \text{si }k\geqslant1\\\\\dfrac{\pi}{2} & \text{si }k=0\end{array}\right.\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-a54857a639c8484a3f8adfec6dc30c44_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[J_{p}=\dfrac{p\pi}{2^{2p-1}}\left[\binom{2p-1}{p-1}+2\sum_{k=1}^{p-1}\left(-1\right)^{k}\binom{2p-1}{p-1-k}\right]\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-6435cf83df1bfa4e8ad6e5e2090e24b0_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}J_{p} & = & \dfrac{p\pi}{2^{2p-1}}\left[\binom{2p-1}{p-1}+2\left(-1\right)^{p-1}\sum_{j=0}^{p-2}\left(-1\right)^{j}\binom{2p-1}{j}\right]\\& = & \dfrac{p\pi}{2^{2p-1}}\left[\binom{2p-1}{p-1}-2\binom{2p-2}{p-2}\right]\end{eqnarray*}](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8af88aff72de817b0c4e4a88e9dfc0c5_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\boxed{J_{p}=\dfrac{\pi}{2^{2p-1}}\binom{2p-2}{p-1}}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-898d88aa005ac29157850616e39dfc20_l3.png)

associe la permutation

associe la permutation  définie par

définie par![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\forall i\in\left\llbracket 1,n\right\rrbracket ,\thinspace\left\{ \sigma\left(i\right)\right\} =C_{i}-C_{i-1}\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-61439e3cbb16bcb344f1ba1da2259123_l3.png)

chaînes. Soit maintenant

chaînes. Soit maintenant  une partie de

une partie de  Notons

Notons  Dire que

Dire que  fait partie d’une chaîne

fait partie d’une chaîne  signifie que

signifie que  Il existe

Il existe  façons de contruire la sous-chaîne

façons de contruire la sous-chaîne  puis, pour chaque tel choix,

puis, pour chaque tel choix,  façons de prolonger celle-ci en une chaîne. Au total, le nombre de chaînes « passant par

façons de prolonger celle-ci en une chaîne. Au total, le nombre de chaînes « passant par  » est

» est

l’ensemble des parties de

l’ensemble des parties de  qui sont de cardinal

qui sont de cardinal  est une antichaîne, de cardinal

est une antichaîne, de cardinal  En particulier pour

En particulier pour

notons

notons  Par définition :

Par définition :  Comme

Comme  on voit en passant aux cardinaux que :

on voit en passant aux cardinaux que :![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[{\displaystyle \sum_{k=0}^{n}q_{k}}=r\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-56fcf77a20ccb3def346b270077fdb49_l3.png)

et pour chaque élément

et pour chaque élément  on considère les

on considère les  chaînes qui passent par

chaînes qui passent par  Ceci représente un total de

Ceci représente un total de  chaînes, car une même chaîne ne peut pas passer par deux éléments distincts de

chaînes, car une même chaîne ne peut pas passer par deux éléments distincts de  (sans quoi il existerait une relation d’inclusion entre ces deux éléments de

(sans quoi il existerait une relation d’inclusion entre ces deux éléments de  ce qui est absurde). Ce total étant majoré par le nombre chaînes, il vient :

ce qui est absurde). Ce total étant majoré par le nombre chaînes, il vient :![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}q_{k}\thinspace k!\thinspace\left(n-k\right)!\leqslant n!\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-39e5a0ee4ae8bd34082c4c24db8a217b_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}\frac{q_{k}}{\binom{n}{k}}\leqslant1\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-4953a1f645e9c49eb1e884b163e2bb2a_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\forall k\in\left\llbracket 0,n\right\rrbracket ,\thinspace\binom{n}{k}\leqslant\binom{n}{\left\lfloor \frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor }\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e4611ed39ae8e90c2d8933c3ca628d61_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sum_{k=0}^{n}q_{k}\leqslant\binom{n}{\left\lfloor \frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor }\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-2a9435892a79bdf8e22054a7df7e16ee_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[r\leqslant\binom{n}{\left\lfloor \frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor }\]](https://math-os.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-63e723f2631b0709e1403c97bd01e488_l3.png)

La formule obtenue pour

La formule obtenue pour